COVID-19 turned Philippine potter Mansy Abesamis’s fears into a community-enriching project called Pottery for the Future.

Mansy Abesamis is a potter, a jewelry designer, a papercut artist, and the owner of multiple artisan brands—most notably Hey Kessy Pottery and Hey Kessy Jewelry. She grew up in Pangasinan, enriched by like-minded people who sourced raw materials from their surroundings and made things by hand. As a child, her first foray into pottery involved receiving and playing with a miniature clay cooking set. She also fondly recalls playing with snail poop that resembled little mountains, reshaping them into dishes, cups, or whatever she imagined.

Since rekindling her love of clay in 2012, she has been honing her pottery making skills and sharing her love for the ancient art form by hosting workshops and selling her “imperfect” creations. Mansy reveals, “Buyers are used to perfect pieces, but in our studio, everything is imperfect—just like the hand that made the pieces and the people using the pieces.”

It Started with a Question

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic struck and initially instilled fear within Mansy’s heart. She shares, “The pandemic made me realize that everything was going digital. Everyone who was surviving was successful in the digital realm, but I’m not a techie. I thought to myself, ‘I’m a potter and I work with clay, which is something very old. How will I survive in a digital world?’”

This worrying thought continued as everything temporarily ground to a halt during the lockdown. But when restrictions were slowly lifted, Mansy started to sell her wares online through Instagram and discovered that there was still a market for it. She realized that “no matter what happens, even if a pandemic hits, the things you choose to stay will stay.”

Fueled by her love for pottery and the burning desire to keep the art form alive, she asked herself, “‘As a potter, what’s my role in this pandemic?’ I thought about it and realized that my goal was to empower other potters. I wanted to tell them that you don’t need to be nervous or anxious that you’ll lose your [source of livelihood] just because [everything is going] digital.” Mansy adds, “I also took my personal experience of being so very worried about pottery. I didn’t want it to just disappear. The fire in me to save pottery and to bring it to the future was so intense.”

Once she had a goal in mind, Mansy wrote it down as a constant reminder of what needed to get done. “The name ‘Pottery for the Future’ became a guide for me, even if it had not happened yet in 2020. [Looking back on the last few months,] I think that [writing it down] worked. Whether consciously or subconsciously, all my decisions and actions went toward that direction.”

Giving Back to the Community

Founded by Siegrid Bangyay and Tessie Malecdan Baldo (who she fondly calls her aunties), Sagada Pottery was instinctively the first studio/community Mansy thought of helping out because of the relationship they had formed over the years. She first trekked to Sagada on her own in 2012, spending countless hours in their pottery studio to learn the craft and find out more about the women themselves. That month-long trip left an indelible mark on her and somehow turned the small town into her pottery mecca, which she found herself traveling to on a yearly basis. Despite the 12-hour bus rides, Mansy did not mind sitting next to vegetables or live animals while traversing unpaved roads. She simply looked forward to reconnecting with nature and spending time with this humble community of female potters.

More than just passing on their ceramic-making knowledge, the Sagada women also showed her the importance of doing things together such as eating meals, going to the forest to harvest mushrooms, and having hot coffee while exchanging stories. Mansy says, “It’s not just about your technique, like how to make the mug or center your clay. It’s more of what the clay bowl does within a community… It makes sense because we would make plates and mugs, and that’s what people would use every time they gathered. These vessels would hold the food they made.”

Coincidentally, a trip to India and Nepal in the same year showed Mansy the unmistakable link between pottery and community. She recalls, “Everything in India was so visually stimulating. Their culture is similar to ours, which is crafts-based as well. I felt that when they wanted to make you feel like you belong, they would buy you tea and put it in beautiful clay cups. That time, I thought to myself, ‘I also want to be like that. I want to gather people.’ But the problem was, I didn’t know how to cook [back then]. So I told myself, ‘Okay, I’ll just be the one to make the vessel for the food or drink.’”

Setting Things into Motion

Once her objectives were set, Mansy reached out to the Sagada women in April, and they were equally excited to sell their handmade mugs and bowls. Unsurprisingly, there were countless hurdles Mansy and her two assistants had to jump over before the initiative could take its first few steps. However, the potter was not dissuaded. “My sister always tells me, ‘You are always five people away from your goal.’ If you ask help from others, they might have what you need [and vice versa]. If you work together, you can reach a goal—even if there’s a pandemic.”

A major challenge was setting up a digital platform for the project, and following her sister’s advice, the self-confessed technophobe asked for help from her friends. She says, “At the time, my skills were so limited, so Dang Sering helped me with the writeup while Soleil Ignacio helped me make the skeleton of the website. When I learned how to make the skeleton, I made a new one. And that’s how the website was born!”

Though Mansy is adept at taking pictures to promote products, the wares were still in Sagada at the time so her aunts had to take the photos. The student became the teacher, guiding the potters how to shoot their wares against a white background or at a certain angle to showcase their beauty. Mansy is happy that they are more active in the digital world, citing that Auntie Siegrid even set up her own Instagram account a few weeks after their tutorials.

After the wares were posted and sold on the website, getting the fragile items to Manila and to its eager buyers became the more pressing concern. “It took some time for the first batch of orders to arrive because there was no public transportation in Sagada. Plus, no one could just go in and out of the place. Everyone was trying to figure things out, so the rules and travel restrictions weren’t set. Every day, it would change,” recalls Mansy. Eventually, the potters found relatives and friends who worked in Manila, had travel passes, and were willing to personally bring the delicate wares to the studio.

Additionally, Mansy and her virtual assistant had to speak to the buyers one by one and share their difficulties in transporting the orders. “Thankfully, the supporters of Hey Kessy Pottery are kindred spirits. They were very understanding of the situation, especially if there were delays. Once you communicate and present the challenges to people, it helps you become a community. We’re in the same storm, but in different boats. Those limitations, challenges, or problems don’t stop us [from working together].”

Extending More Help

“After I started working with the Sagada potters, I wanted to work with more potters in the Philippines. [I wanted] to create a map,” Mansy explains. The opportunity came when Typhoon Ulysses struck the country in November 2020. Bicol was one of the provinces that was badly ravaged by the tropical cyclone, and weeks after, some parts of the region still did not have electricity. Mansy wanted to help out in her own way, and, through a common friend, found a family from Tiwi, Albay who were selling terracotta pots. “What I did was I used some of the money from Hey Kessy Pottery to buy their pots outright. That was what other small businesses needed at the time—they needed capital. Plus, they couldn’t make new wares because they didn’t have electricity in the studio. It all worked out since the family had lots of pots to sell, and there are now a lot of plantitos and plantitas in Manila.”

It took Mansy only one week to mobilize the Bicol project, laughingly describing herself as going into beast mode to promote the project, connect with people who could help, and figure out how to bring the pots to Manila. “My emotional investment was so high. I was like, ‘I’m gonna make this work!’”

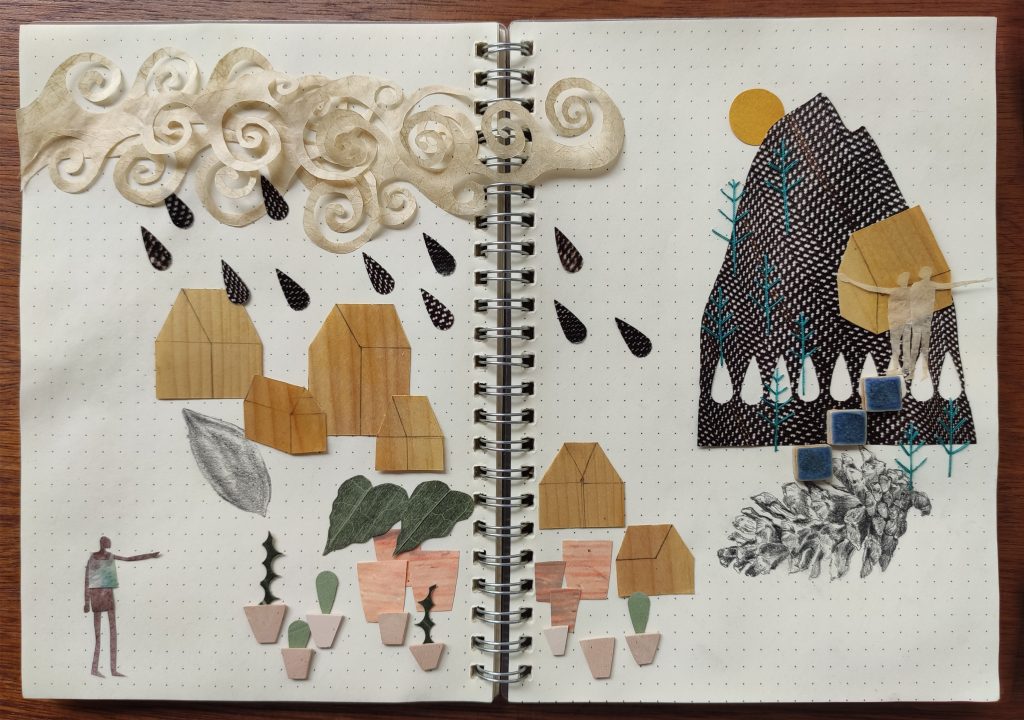

The Manila-based potter was not worried about the Bicol pots competing with the existing Sagada ceramics, since the materials used were different. Mansy shares, “Potters have very unique clay recipes, so it really looks different per province. It’s like a diary of where they’re from. They use locally sourced soil and just add something else.” As such, the orange-colored matte pots from southern Luzon would stand out beside the blue-glazed pieces from the north.

Strengthening Ties Through Art

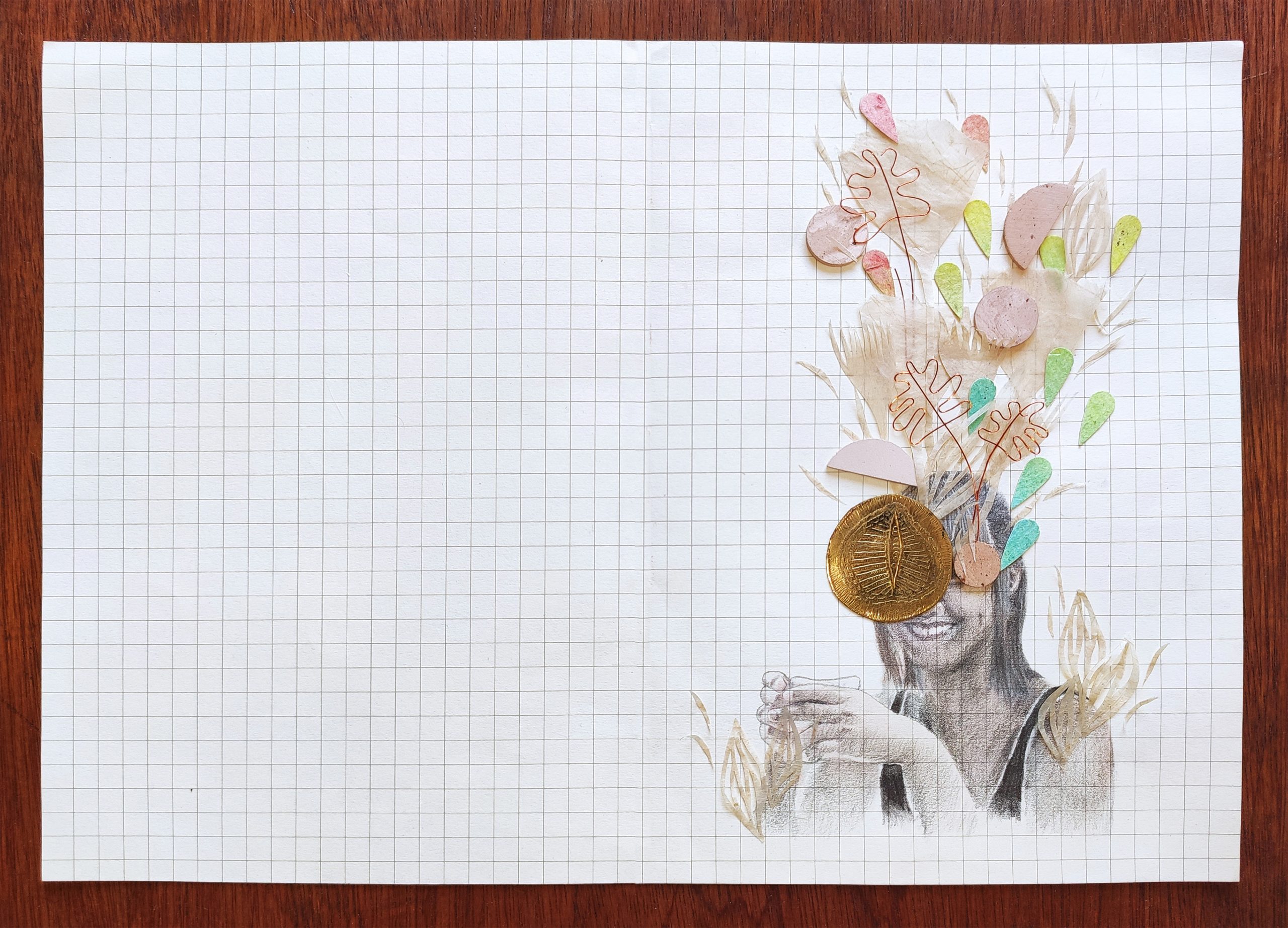

Mansy was never one to shy away from organizing community-building projects. Over the years, she has set up a community art festival (2015 and 2017), and put together an all-women ceramics exhibit (2019). Both events introduced Mansy to creatives from various fields, and allowed her to be exposed to different points of view. For the latter exhibit, Mansy invited graffiti artists and street artists to design her ceramic plates. “I wanted to show that pottery wasn’t limited to just one color, and to show that modern art forms can be combined with old craft forms. Their styles and techniques were different [from mine], so I learned so many new and fascinating things.”

Though gathering in large groups and traveling are unlikely to happen in the near future, Mansy keeps the spirit of community alive in her own ways. She stays in touch with her Sagada family by chatting with them through Facebook Messenger, and plans to give them more workshops to help them improve their photo-taking skills. Meanwhile, Mansy continues to foster community growth by collaborating with people that she wouldn’t normally work with. Her most recent collaborations include the “Hawak Mo Ang Kapalaran Mo” coffee dripper for Commune, and the “You Are Home” exercise board for Balbo. The potter shares, “When you work or collaborate with other people from different backgrounds, it’s a good way to have fresh ideas and widen your world.”

Aside from collaborating with others, Mansy turns to other artists from Studio Kapitbahay to keep her mentally, physically, and emotionally healthy. “I love how I get to be exposed to other art forms through my studiomates. There are visual artists, designers, illustrators, graffiti artists, architects, a director, a toy maker, and a beer brewer… These people have become my quarantine family because I live alone. We’re all together in one bubble with our separate spaces but we share one backyard, so we became a small community. It helped us survive everyday life in the pandemic. We get to eat together and celebrate birthdays together. Once, we even took a trip to Makati and BGC while riding our bikes. It was so empowering because I got to go to those places without riding a car.”

Mansy is grateful for how these fellow creatives helped her well-being, and how the arts in general saved the world in 2020. “At the height of the pandemic, everyone was emotionally and mentally relying on the arts to survive, whether it was through looking for a painting or a postcard to buy, a movie to watch, or music to listen to. Art helped people get through a difficult day. If this is the case, then [as artists], we should give importance to the kind of work we’re producing.”

Stepping into the Future

With COVID-19-related concerns still looming on the horizon, Mansy tries to see the silver lining in the situation. Even if public transportation hasn’t resumed in Sagada [as of writing this article], the provincial studio has added two more potters and are all motivated to create more wares. Mansy is amazed by the breadth of the digital platform, saying, “It was discouraging for the potters when there were no tourists coming [into Sagada] and their wares were just sitting there. But now that the creations have been shared online, the platform has been used to expose their wares and reach more people. [Hopefully,] more people will make, more people will believe in themselves, and more people will believe that their profession will survive in this world.”

Mansy dreams of making pottery available to more Filipino potters and enthusiasts, no matter how old they may be. “My wish is to have more potters join the club, especially those without access to reliable internet, or the older ones more focused on making the wares.” She adds, “Aside from helping sell the potters’ wares, I also plan to teach more virtual workshops. Not just for people to learn how to make them, but so that they could understand the art form. Like when someone forms the clay [into different shapes], it doesn’t necessarily mean the pieces will survive in the kiln. I also mention what it does when you have your own cup, and when you share it with other people you love. Especially now that we’re away from our loved ones. We are isolated and we can’t gather just like before.”

Since the lockdown began in 2020, Mansy has taught several online workshops including private sessions for companies. She was even able to teach students living in other provinces such as Cagayan and Cebu, sending their clay kits and receiving their pieces via local courier. This was something she never thought was possible pre-pandemic. The potter also enjoys teaching kids, revealing, “I feel it’s important to hold workshops for kids because when you expose them to pottery, they will protect it when they grow up. They’ll know the importance of the art form.”

Mansy is aware of the limitations of selling pottery online and hosting virtual classes, but she believes the lockdown has proven that these can be done successfully. The owner of Hey Kessy Pottery says, “Though a potential buyer can’t feel the weight of a ceramic ware in his hands or closely inspect it, we try to fill the gap by providing its dimensions on its website and sending the person additional photos when available.”

As for teaching pottery online, Mansy shares that some technical skills may be harder to teach, but it’s all about finding creative ways to explain them. For example, the notches of a toothpick (included in their clay kit) can help a student figure out how thick a piece should be. Additionally, Mansy reveals that going closer and looking at the screen directly makes it seem like she’s right beside her students. She calls on individuals to recite and share their progress, much like how she does it in real life. Though Zoom fatigue and unstable internet connection may be considered as two of the biggest challenges to online learning, the opportunity to try pottery in the comfort and safety of one’s home is becoming a draw to more people curious about the age-old craft.

Thanks to Mansy’s efforts of bridging the gap between this analog art form and the digital world, the future of pottery looks promising.